The Parenting Police Are Watching

We should openly break the rules and normalize imperfect parenting.

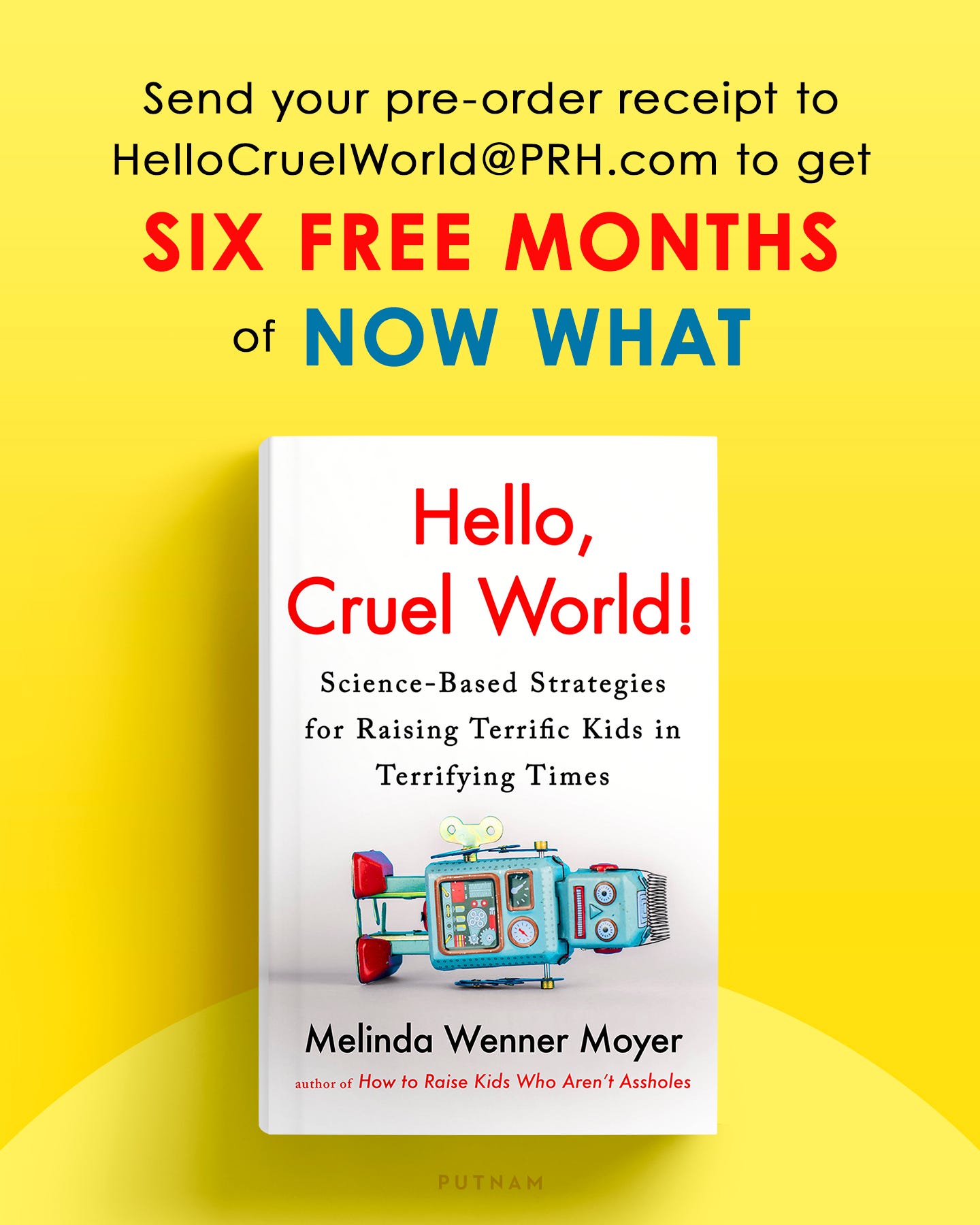

Before I jump into today’s topic, a reminder that my book Hello, Cruel World! comes out in just SIX WEEKS! The Big Idea Club has picked my book as one of its “Must-Reads” for May, and the the Child Mind Institute loved it so much, they invited me to be the featured guest at their annual spring luncheon next month, where I’ll follow in the footsteps of recent past guests Dr. Becky and Emily Oster.

If you haven’t already pre-ordered my book, please do. Pre-orders are so important because they signal early interest and demand, which can dramatically influence a book’s success. Bookstores use pre-order data to decide how many copies to stock and how prominently to feature books, and pre-orders count toward first-week sales, which are hugely important in terms of making bestseller lists. Essentially, a strong pre-order showing can mean the difference between a quiet release and a breakout launch. And I want to get this book in the hands of as many parents as possible because I think it could help our generation of kids grow up to be resilient, empathetic, mentally healthy and astute adults.

PLUS, if you pre-order and send your receipt to HelloCruelWorld@PRH.com, you will get six free months of paid content to Now What!

In Slate this week, the journalist Stephanie H. Murray has a fascinating story exploring the controversy over parents using baby monitors and FaceTime to keep an eye on kids while they leave the premises. “It’s become a matter of routine that when we stay in hotels as a family, my husband and I will head to the lobby, bar, or restaurant with a phone or laptop set up as a makeshift monitor after our children — we now have two — go down for the night,” she writes.

Murray didn’t think much of these choices until she learned what happened to parenting influencers Matt and Abby Howard when they shared on social media that they had done the same thing on a cruise. The backlash was swift, and according to People magazine, “several YouTube and TikTok creators made videos detailing safety concerns about the situation.” People expressed worries that the kids could be abducted, a fire might break out, or “some other horrific tragedy might unfold that the distance from dinner back to the cruise cabin would prevent the couple from addressing,” Murray writes. Parents have been arrested for similar transgressions.

I’m not going to evaluate the validity of these specific claims about risk, other than to say that the chance of any of these tragedies unfolding in such a way that parents couldn’t intervene in time to help their kids is likely very, very low. And I will be honest, I have also used the baby monitor hack on occasion, in ways that feel totally safe to me, and I don’t regret it. But rather than focus on this particular scenario and its moral acceptability, I think it’s far more interesting to zoom out and consider what this controversy illustrates about the expectations and norms of modern parenting.

There’s a pervasive belief today that it’s not okay to do things for yourself as a parent if means taking anything away from your kids — or if it there is merely an infinitesimal chance that your choice could take anything away from your kids. Parents are expected to always put their children first, to exhibit constant devotion and be willing to make any and all sacrifices to ensure that kids are never put at risk. And we’re not merely supposed to do whatever is needed to ensure our kids’ safety; we’re also supposed to do whatever is needed to ensure our kids’ success, comfort, happiness, and self-esteem.

Murray writes:

Sitting in a darkened hotel room for nights on end during your vacation while a restaurant serves drinks a couple floors below — for many, that seems to just be expected. To even consider risking a child’s safety, even a little bit, for the benefit of the parent is itself an indication of bad parenting. “You shouldn’t take any action on the grounds that it would be better for you,” Sarnecka said, describing this mindset.

In her article, Murray cites fascinating research that suggests that our perceptions of children’s safety are strongly influenced by moral beliefs. When we believe that parents have made a parenting decision for selfish reasons, we perceive their decision as more dangerous and less acceptable than if they made the decision for other reasons.

Here’s Murray again:

In 2016, Barbara Sarnecka, a professor of Cognitive Sciences at the University of California-Irvine, conducted a study which asked survey respondents to assess the risk a child was in after having been left unsupervised by their parent for a short period of time. In each vignette, the reason for the parent’s absence varied. In one, the parent is hit by a car and knocked unconscious while returning a library book. In another, the parent pops inside the library to pick up a paycheck. In a third, the parent leaves the child to meet a lover behind the library.* The risk to the child should not be affected by the reason for the parent’s absence—in fact, in each, it’s likely minimal—but according to the respondents, it was.

“Everybody definitely thought that the kids were in more danger if the parent chose to leave than if the parents got hit by a car and knocked unconscious,” Sarnecka told me. “The more morally outraged people felt at the parent, the more danger they claimed the child was in.”

The implications of these findings are fascinating. It’s not just that putting kids in danger is immoral; it’s that immoral decisions are also dangerous for kids. What a clever way to ensure that parents (especially mothers), who of course love their kids, will stick to prescribed roles! Our society strongly moralizes the practice of parenting, and judges and punishes parents (especially moms) for making choices that go against the accepted code. It’s why my good friend felt as if putting her daughter in daycare made her a terrible parent and why mothers who formula feed feel they are harming their babies. (I’m reminded, too, of my interview with Nancy Reddy, who pointed out that societal expectations for mothers always intensify women are making progress in society and starting to compete with men.)

This moral code isn’t anything close to rational, though. We judge parents for stepping 200 feet away from their kids to sip a drink at a bar — all while watching them carefully on a video monitor — yet we don’t judge parents for driving their kids to school, even though the chance of a car accident is much higher than the chance of tragedy befalling sleeping kids in a hotel room. It’s far more accurate to say that we judge parents for taking certain kinds of risks — risks that seem self-serving — but don’t judge parents for taking other kinds of risks.

As the authors of that 2016 paper wrote:

People may overestimate the danger to unsupervised children in order to justify their moral condemnation of the parents who allow the children to be alone. Thus, exaggerated fears of harm and increasing moral prohibitions form a sort of self-reinforcing feedback loop. We will ultimately suggest that much of the recent hysteria concerning danger to unsupervised children is the product of this feedback loop, in which inflated estimates of risk lead to a new moral norm against leaving children alone, and then the need to justify moral condemnation of parents who violate this norm leads in turn to even more inflated estimates of risk, generating even stronger moral condemnation of parents who violate the norm, and so on.

Because today’s parenting moral code is so strict, Murray writes, parents who break the rules often do so as quietly as possible, to avoid repercussions. Just look at what happened to Matt and Abby Howard when they publicly shared what they did on their cruise! This strict moral code serves to silence defectors, which only further strengthens the code, as impossible or unfair as it may be. “The world of manageable parenting hasn’t entirely disappeared, but moved behind closed doors,” Murray writes.

One of the key reasons I write this newsletter is because I think it’s essential to push against this unfair status quo and normalize the messiness of modern parenting — to reveal and celebrate imperfection, rather than keep it hidden. I want to shatter the polished façade of perfect parenting and make space for the glorious, necessary mess. I want parents to understand that it can actually be good when we screw up, put ourselves first, and fail to ensure our kids’ success, comfort, happiness, and self-esteem all the time.

I’ve written before about whom strict parenting norms and expectations typically serve, and let me be clear: It is not kids, and it is not parents (especially not mothers). When we believe we have to follow all the impossible “rules” of intensive parenting or else, we end up feeling miserable, worried, and ashamed — trapped in a system that demands our sacrifice and offers no grace in return. We deserve better, and our kids do, too. And we should remember that when we thoughtfully break the rules, we’re not failing. We’re fighting back.

Congrats on the early accolades for Hello, Cruel World, Melinda! And thank you for today's post, which, as usual, gives voice to an incredibly important issue. Did you read Kim Brooks' "Small Animals: Parenthood in the Age of Fear"? It's a few years old now, but I loved it and still think of it often.

THANK YOU for this. As Europeans we practiced what some of my US relatives referred to as "extreme free range parenting" so you can well imagine the clashing of cultures whenever we brought the boy over to visit grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins. Spouse and I tried really hard to not be too dogmatic or stand out in really annoying ways ("when in Rome..." you all know the saying). But sometimes there was just too much idiocy going on.

I recall my mom taking me out shopping for clothes that fit post-partum when I was visiting with the five-month-old baby. He slept peacefully in the giant buggy– too big for the fitting room– borrowed from my sister-in-law, I struggled in and out of various items while the proud grandmother collected a range of sizes while keeping half an eye on the buggy. THIS WAS NOT GOOD ENOUGH and we got a stern talking-to from the salesperson, floor manager, and a department store security guy. My mother, who raised four kids in the US, was taken aback (and we left empty handed).

Standard eurostory over. My husband and I were also fans of a nightcap in the hotel bar, or a late dinner, or even just reading in the hotel lounge while our toddler slept happily upstairs. Until one time when the fire alarm went off in a hotel in Chicago. Elevators out of service. My husband ran up eight flights of stairs, boxing through the people coming down, to grab Mr Sleepyhead while I endured both terror of the unknown and being castigated by hotel staff and guests alike as the worst mother on the planet. Of course it was a false alarm. But we were less relaxed about lobby drinks (in any country) after that.