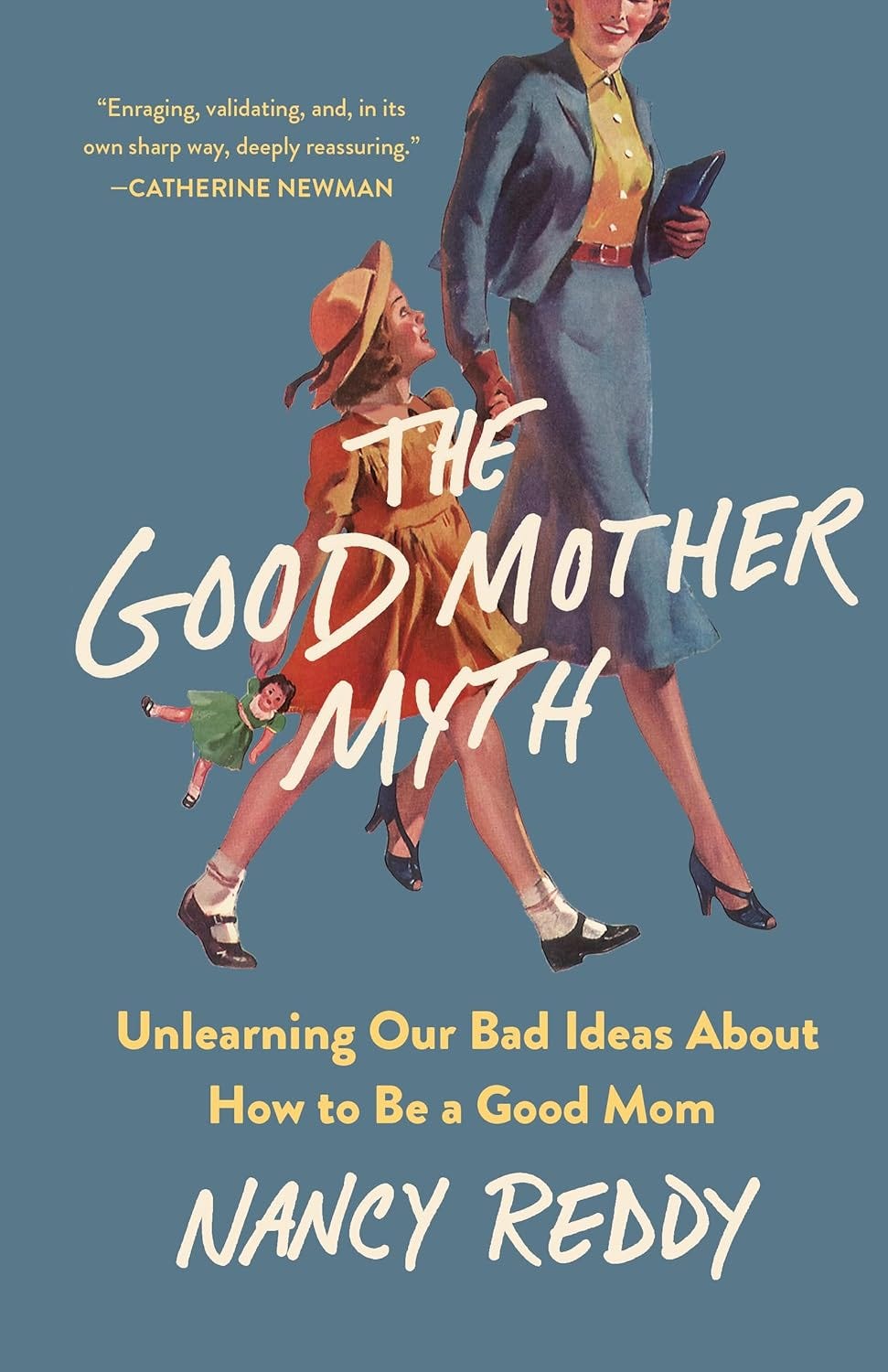

A few weeks ago I finished Nancy Reddy’s marvelous new book, The Good Mother Myth. I honestly can’t say enough good things about it. It is an incredible in-depth exploration of how our society came to adopt so many unrealistic and unfair expectations of mothers. It is part vulnerable, honest memoir and part investigative journalism, revealing the various ways in which our beliefs about motherhood are based on flawed reasoning, bad science, confirmation bias and sexism.

I was thrilled when Nancy agreed to do a Q&A about the book for Now What. We talked about the important (but largely hidden) flaws in early child development research, the relationship between social progress and parenting norms, what parents really need to know about attachment theory, and more.

I loved every page of The Good Mother Myth, and I highly recommend you read the whole thing if you’re curious about why parenting today is so damned hard — and why we should take a lot of older child development research with a grain of salt.

Nancy, what inspired you to write The Good Mother Myth? How did your own experiences as a new mother shape your decision to write it — and your reporting?

Before I became a mother, I thought of myself as someone who could figure pretty much anything out, if I worked hard enough and read the right books and consulted the right experts and learned the right rules. So I approached pregnancy and birth and early motherhood that way, and wow did that not work out! The book began as a really personal inquiry: why was motherhood, this thing I’d been told was “the most natural thing in the world,” so incredibly hard for me?

The questions evolved as I researched and wrote, and so did my own understanding of what had happened to me in early motherhood. As I worked, I came to realize that, although there are some parts of caring for a new baby that are just inevitably difficult (hello, sleep deprivation!), the bad ideas we so often bring to motherhood make it much harder. My own bad ideas were buried so deeply that it took me years to even unearth them — the idea that when I gave birth, I would be transformed into an endlessly patient, constantly loving mother, that I’d just automatically know how to care for my baby, that being the mother meant I was the one responsible for that work. In the end, the book is a project of figuring out where those bad ideas came from and how we can get better ones.

I had one of those "holy shit" moments reading a sentence of yours very early on in your book. You wrote: "Our standards for mothers have always increased at just the moment when women were making gains in public life." Can you share a few examples of this from history and speak a little to how it relates to today's intensive parenting norms?

It’s shocking, right? It’s one of those things that once you see it, everything looks different. The insight originally comes from Andrea O’Reilly, a foundational thinker about feminism and motherhood. I think about this phenomenon through the generations of women in my own family.

My grandmother was a literal 50s housewife, but she’d gone to college and gotten a degree in economics before being told that she’d never really be able to have the career she dreamed of. She didn’t get married until after World War II, but millions of women just a bit older than she was had worked as part of the war effort and sent their children to state-supported daycare — and then once the war was over, they were told that the patriotic thing to do was to go home and raise their babies.

My mother was part of the generation of women who started outpacing men in college attendance and graduation. (She was so career-focused in her twenties that when she called her mother to say she was pregnant with me, my grandmother responded, “don’t tell me — you’ve been promoted again?”) And that’s literally the generation of mothers who were studied by Sharon Hays, the sociologist who first coined the term “intensive mothering”!

At each moment when women are making progress and starting to compete with men, suddenly our expectations for mothering nudge ever higher. My mom spent more hands-on time with me and my sister than her mother ever did, but because she was working and sending us to daycare, she worried that it wasn’t enough.

And we’re in a moment of profound cultural backlash now. That shows up in everything from our electoral politics to social media to our homes. Women married to men are increasingly out-earning their husbands — but in most cases, they end up doing more domestic labor and caregiving, too!

You do such an amazing job of picking apart the key mid-century studies that established the pervasive belief that the love and single-handed devotion of a mother is crucial for a child's well-being. This included the "cloth mother" experiment by Harry Harlow and all the attachment theory work by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. To what degree do you think that the conclusions drawn from this work were colored by confirmation bias and sexism? Can you share a few examples?

Confirmation bias is such a key part of the problems with this research! John Bowlby was actually incredibly clear about this in his work; he basically settled on a theory about children’s development at the very beginning of his career and spent the rest of his life seeking out the evidence that would confirm it. After the end of World War II, the World Health Organization tasked him with traveling around Europe to investigate the mental health of children impacted by the war. Before he left on that research trip, he wrote to his wife that he worried about “the danger of racketing about seeing too many people — half of whom [would] be pretty stupid.” When he met people whose ideas he didn’t agree with, he basically just put down his pen. When he got to Sweden, for example, he found that the government was trying to support troubled children and their families by pairing psychiatric treatment with social programs to address homelessness, addiction, and unemployment, but those programs got barely a mention in his report. He’d decided before he even set out that mothers’ care and attention was at the center of a child’s healthy development, and he declined to include or even really consider any evidence that ran counter to that theory.

You can also see confirmation bias in the design of the studies that underlie Mary Ainsworth’s attachment styles research. After working with Bowlby in London, Ainsworth spent some time in Uganda, where she got a grant to observe childcare in small villages. But, like Bowlby, she’d already decided that mothers were the ones who mattered, and even though she observed shared care in those communities — grandmothers, aunts, siblings, fathers all participating in different ways in caring for children — she didn’t include that care in her theory. She then spent a year observing new mothers in Baltimore, and her team went at all times of day to observe the care the mothers were providing at different moments — except in the evening, when the fathers would be home. If you design your study so that you only observe mothers, and then you conclude that the mother’s care matters the most, you shouldn’t call that a finding. You’ve baked the desired result right into your design.

What do you want parents today to understand about attachment theory? What are a few of the key things you learned about this body of work in your reporting?

In the book, I focus on the origins of attachment theory. Bowlby and Ainsworth were very clear that they believed that a “warm, intimate, and continuous” relationship with the mother was an essential foundation for the child’s whole life. (Bowlby has like one footnote where he says “mother or mother-figure,” but it’s very clear that he meant the mother. For one, he was a lifelong campaigner against daycare and working mothers.)

The most high-level insight of attachment theory — that children need attentive care from a loving adult — holds up, but there’s no real scientific reason to think it has to be the biological or gestational mother, or that a child is harmed by having more than one caregiver. The foundational studies just aren’t nearly as solid as we’ve been led to believe. Folks who are real advocates of attention theory often behave as if it were widely accepted and uncontested until a bunch of grumpy feminists discovered it in the 80s and 90s, and that’s not true. It was controversial in its founding. A decade after Bowlby’s original report, the World Health Organization published a follow-up, and it was full of prominent researchers discussing the limitations of his work. Bowlby was really good at consolidating support for his theory, and his version of things is the one that’s largely come through to today. But the fact that it’s widely accepted and taught doesn’t mean the science is accurate.

Can you talk a bit about Margaret Mead's work and what it suggested about children raised by "many warm, friendly people"? In what ways does her research challenge intensive parenting norms?

Mead’s work was such a bright spot in this research! I kept coming across her name as I was working on the other chapters — she was one of the respondents in the WHO report I mention above, she enlisted Dr. Spock (the subject of another chapter) as her pediatrician when he was first starting his practice — and I finally wrote to my editor and said, we need a Mead chapter! She was part of the intellectual circle of the time, and her own parenting was really shaped by her research–and she parented so differently than what Bowlby advocated!

Mead argued that what children needed wasn’t the constant devotion of one perfect mother but the love and attention of “many warm, friendly people.” When she did her research in Samoa, she observed shared caregiving, and she brought that idea back with her to the US when she ultimately became a mother. Even though she was married to the father of her child, they never lived on their own, but instead formed what she called a “composite household” with other families.

Her daughter, Mary Catherine Bateson, wrote a really beautiful memoir of her childhood, and it’s clear that Mead wasn’t a perfect mother. She traveled a lot, she worked a ton, and she often left her daughter in the care of others, sometimes for an extended period. But when she was with her daughter, she was deeply present, and it’s clear that they were very close. Mead took seriously the task of building community around her child, and instead of trying to get her daughter the best of everything, she worked to improve things for all the children in her community. That feels like an incredibly powerful lesson now, especially when so many upper middle class white parents are obsessed with optimizing every aspect of their children’s lives.

Towards the end of your book you briefly describe a study conducted by Seymour Levine that you said has given you a lot of comfort over the years. Can you talk a bit about it and what you have taken from it?

The rats! I’m so skeptical through much of the book about the lessons we’ve learned from monkeys and tried to apply to human babies, and I definitely think there’s a danger in trying to leap from animals to humans, but I couldn’t resist sharing this one lesson from rat research because it really has been such a comfort to me.

Levine raised his rats in one of three conditions: 1) baby rats and mom, undisturbed; 2) the baby rats are occasionally taken out and handled by the scientists, which stresses them a little; and 3) the baby rats are occasionally taken out and given little electric shocks, which is of course very stressful! And it turns out that the worst conditions for raising a healthy rat, in the long term, is actually 1), where the mother and babies are left blissfully together, even though that’s more or less what Bowlby was advocating. Thinking about those baby rats surviving stress and minor electric shocks has been immensely comforting to me when I reflect on the times when I’ve messed up with my kids. They don’t need us to be perfect; they can survive the shock of our little failures. (And unlike Levine’s research team, I apologize when I snap at my kids or otherwise stress them out.)

How has the process of writing The Good Mother Myth shaped your parenting?

Writing this book required me to go really deeply back into the hardest parts of early motherhood, as well as some really hard parts of my marriage. Because I was able to look at all of that from some distance, it helped me to develop a lot more self-compassion. There were so many points writing this where I really did feel like I was sitting next to that exhausted new mom version of myself, saying, you’re doing your best, and this will all turn out okay. And I hope the book helps other parents extend that self-compassion to themselves as well.

I also felt the book made a number of very valuable and valid points. However, I don't think that many of the recent critiques of attachment theory give sufficient credit to another part of the context in which this theory was developed. Yes, there is a patriarchal society, no question. But there was a prevailing belief that if children were kept clean, well feed and germ free they would be fine-part the behaviorist tradition. Thus, in hospitals parents did not stay with their children but only had restricted visiting. The classic film "Laura Goes to the hospital" by Bowlby associate J Robertson showing the heart rending distress of this child's hospital stay without her parent did a lot to change hospital policy. It is really is because of attachment theory that parents can stay with their children when they have their tonsils out. And as a clinician, I can also say that attachment theory has been invaluable in helping many seriously traumatized children. So yes the critiques of attachment theory are important, but it is also important to give notice to the other parts of the cultural context that attachment theory developed

This was such a great read! So many good insights. Thank you