Reimagining Boyhood

A Q&A with Ruth Whippman about her new book BOYMOM.

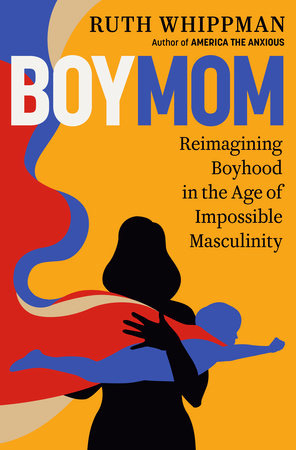

I’m absolutely thrilled to be running an interview today with journalist Ruth Whippman, whose wonderful book BOYMOM: Reimagining Boyhood in the Age of Impossible Masculinity comes out today.

Ruth sent me an early copy of her book copy months ago and I inhaled it. It’s a book I’ve long been waiting for — research-based, thoughtful, and beautifully written, exploring many of the thorny issues I’ve wondered and worried about as a feminist raising a son today. I can’t recommend it enough, and I really, really hope it sells like hotcakes.

I love the book so much I’m running a June giveaway for my paid subscribers who live in the United States. Enter here to win a copy of this book as well as Elissa Strauss’s fantastic new book When You Care (I’ll be running an interview with Elissa later this month, stay tuned!).

Without further ado, here’s our conversation. We talked about gender norms and pressures, video games, incels… so much. I also recommend subscribing to Ruth’s thoughtful new Substack, I Blame Society.

Ruth, what inspired you to write BOYMOM?

I was about 8-and-a-half months pregnant with my third son when the #Metoo movement exploded. Every day seemed to bring more horrific news about men. It started to feel like — is every man in America a sex offender? How did we get to the point where this was so normal?

It was a really complicated time for me — as a feminist, #Metoo was exhilarating. It felt like the entire discussion about gender and power had been turned on its head and women were finally wresting control of the conversation. But as a mother of sons, I was extremely conflicted and scared. I was asking myself: where are we going wrong with raising boys on a systemic level that means that male bad behavior is so normalized, and how can we do better, but also, what does it mean for an entire generation of boys to grow up with that conversation going on in the background? How will it affect them psychologically and emotionally to hear themselves talked about as basically just these predators in waiting?

So my aim with the book was to really sit with all of those conflicted feelings and questions and to try to find out what is really going on with boyhood in this extremely fraught cultural and political moment. The book is partly memoir, looking at a really challenging time in our own parenting journey — the first 5 years of my third son’s life while we are navigating raising three rambunctious boys, a pandemic and diagnoses of neurodivergence for all of them amongst other things with the backdrop of the whole cultural conversation around toxic masculinity — plus reporting on boys’ lives all around the country and cultural analysis to try to really dig into all those questions and conflicts. I went to all kinds of places in my reporting, including a boys’ residential therapy center in Utah, a conference for boys accused of campus sexual assault, and a fancy boys’ private school in New York that is trying to address toxic masculinity norms as well as talking to boys and experts of all kinds to try and make sense of it all.

One point you make early on in your book is that male babies are actually more physically delicate, and emotionally reactive and vulnerable, than girls are. This seems concerning considering that we often treat little boys as if they are the exact opposite, assuming they don't need as much emotional or physical support as girls do. Can you talk a little bit about the implications of this research and how we might want to consider it as we raise boys?

This was one of the most surprising things that I learned in my research. When a baby boy is born, his brain is a month to six weeks behind a girl’s in right-brain development. It’s easy to oversimplify the neuroscience, but broadly, this is the part that is responsible for emotions, attachment and emotional self-regulation. Because of this relative immaturity, baby boys actually need more intensive nurture and support from their caregivers than baby girls in managing and regulating their emotions, and they need it for longer.

But without realizing it, we subtly socialize boys in the exact opposite way: We see baby boys as tougher, stronger and angrier than baby girls and handle them more roughly. This pattern continues throughout childhood with adults projecting more “masculine” qualities onto boys of all ages and giving them less nurturing attention and spending less time listening to their feelings and talking about emotions and instead doing more things like roughhousing and wrestling with them. (I’ve lost count of the number of times that as a mother of boys, men have explained to me that boys “need” more roughhousing and physical play — but they actually get plenty of that already. What boys urgently need is more emotional nurture and support with relationships.) Boys need more care, but get less, and this double whammy leads to all kinds of problems further down the line.

It's so hard to parent a boy right now — on the one hand, it seems hugely important to challenge harmful stereotypes and expand our boys' understanding of what it can mean to be a boy. On the other hand, boys who reject gender norms can be ostracized and bullied. What balance do you strive for in raising your own boys? How do you help them expand their perspectives and self-identities without getting punished? Is that even possible?

I agree — it’s a really hard balance. In a strange way now, gender stereotypes and norms are almost more rigid for cis boys than they are for any other gender group, and the costs of breaking them are high. I write in the book about how I grew up with a feminist mom of the 1970s-second-wave flavor, and lots of things were forbidden — no pink, no Barbies, no make-up, etc. Overall, I’m glad my mom had this value system, and I think the hardline approach made sense at the time, but I think that the deprivation did make me feel different from my friends and crave these things in adulthood.

With my boys I’ve tried to take an approach less of forbidding things or forcing them to break gender norms in a way that might feel embarrassing to them, and tried to focus more on adding stuff in. Exposing them to more options (toys that focus on nurture, books/TV/ movies etc that are about friendship and relationships for example) and to focus on connection and make a real effort to talk with them about emotions — their own and other peoples’.

Can you share your thoughts on why boys are often so drawn to video games and how video game culture shapes their social lives? How do you help your own boys find balance between their screen-based lives and their "real" lives?

Firstly, video games are designed to be addictive and those designs are very effective. But I think there are a lot of deeper things going on there too. There’s a lot of data that shows that boys are increasingly retreating from the real world into a virtual one, and spending less time socializing in real life and more time on screens (this is a significantly worse problem for boys than girls). I think this is partly because socializing can be quite fraught and sometimes unrewarding for boys in real life, and so it is easy for boys to use screens as a kind of social crutch and to avoid the the anxiety of face to face connection. We don’t teach boys relational and social skills in the ways that we very naturally do for girls and we don’t really give them role models for deep connected friendships in the way that girls get them. Plus, masculinity norms teach boys that human interaction is essentially competitive rather than cooperative, and that vulnerability and intimacy are effeminate or humiliating. So real-life comes with anxieties and a feeling of always having to be “on guard” — sometimes it’s easier to just rely on a screen to smooth the edges.

I think also boys are fed a cultural story that they need to be these uber tough superheroes. Masculinity norms demand that they be strong and tough and manly and heroic, and often in their real lives they feel as though they can never measure up. Video games give boys a chance to feel powerful and competent and like the heroes they want to be in a way that they often don’t get to in the real world.

For your book, you spent time talking to incels, too, which couldn't have been easy — I really admire your curiosity-driven approach. You ultimately concluded that incel culture is "not an aberration, but perhaps the most extreme, but still logical, conclusion of many cultural, social, political and parenting threads in boy culture." Can you explain and unpack this idea a bit?

Thank you — yes, it was a really challenging experience spending time on incel message boards and talking to incels directly in interviews. Part of me was very unsure whether I should be engaging with them at all, or giving them a platform given their pretty horrifying history of misogyny and violence. In the end, I decided it was important to listen to what they had to say because I think they represent a kind of extreme manifestation of lots of more mainstream trends in boy culture and socialization, including a super-online culture and extreme loneliness amongst other things.

I went pretty deep with two guys in particular and they both surprised and challenged me in different ways. I was expecting incels to be these totally fringe, almost freakish characters. But when I spent time with them and really tried to understand and unpack the factors that had driven them to the manosphere, the things they were telling me were surprisingly similar to what the so-called “regular” — i.e. non-incel — boys that I interviewed also talked about. One of them was feeling that society’s standards for masculinity were basically just impossible and that they carried around this constant feeling of inadequacy. Also, a profound sense of loneliness. This was a theme that came up over and over with boys that I talked to from all backgrounds: that masculinity norms make it really hard for boys to be emotional or vulnerable with their friends — something that really gets in the way of deep connection.

I was really surprised to see that incel message boards — as well as being some of the most repellent, misogynistic, hate filled places imaginable (many of the posts and discussions on the message boards are truly horrifying) — were also one of the few spaces that I found in my research where men and boys were able to be emotionally open and vulnerable with each other and there was a lot of genuine tenderness and support between the guys on there. It was almost as though, because the incels had kind of given up on the possibility of ever living up to society’s standards for masculinity, it freed them up to throw away those norms all together and just share their feelings and offer each other support.

The whole experience of talking to incels was a series of complicated paradoxes that challenged me deeply and which I unpack in more detail in the book. But it definitely made me realize that if we don’t want boys to look for belonging and connection in the manosphere, we urgently need to provide ways for them to find it elsewhere.

What's a surprising way in which the reporting you've done for your book has changed your parenting?

I think the biggest thing was how much empathy it gave me for my sons and how hard this system is for them, too. I had always seen patriarchy and sexism as things that benefitted boys and men at women’s and girls expense, but now I see how much they harm boys too. This is kind of a whole mindset which allows me to connect with my boys more and to listen to them better, and has given me a whole new way of seeing the world.

On a more practical level, the male vulnerability research made me super aware of really connecting with my boys and seeing their outbursts as emotional rather than discipline problems, and trying to treat them as sad, not bad. There’s a ton of research that shows that parents talk about feelings with daughters far more than with sons and are far more likely to see their sons as “angry” rather than sad. Most of us do this completely without realizing it. So I am trying hard to notice how that shows up in my own parenting and to really try to correct for it.

And really prioritizing connection — with us, with friends, and trying to make sure they have regular screen-free time with friends. The last thing any American parent probably needs in this moment is more guilt about screens (if you want us not to use screens as childcare, give us some affordable childcare!), so I try to view this as less about restricting screen time and more about prioritizing connection in the real world. This can sometimes involve pushing through some excruciating feelings saying no when they and their friends beg for screens on playdates, but it’s usually worth it in the end.

yay!! I want to talk to Ruth about this book myself; I think I'm waiting to figure out what my questions are. Raising boys can be a little lonely and fraught (in addition to the good things!) and then the weirdos out there make it seem like we are all freaks who want to marry our sons.

This just nailed me. My 17-year-old, neurodiverse manchild is so lost just now. He's always been a sensitive soul, and the society where we live does not value this in young boys / men. He can't fit in with the machos (and doesn't try), so doesn't get "girl attention" either. The last 8 months have been just a lot of sadness –– which my husband usually experiences as anger directed at him. Our tiny family spends a lot of energy untangling all these emotions.