What Kids Learn From Us About Success

Psychiatrist Dr. Jessi Gold on why some kids become overachievers — and what parents can do to broaden their mindset.

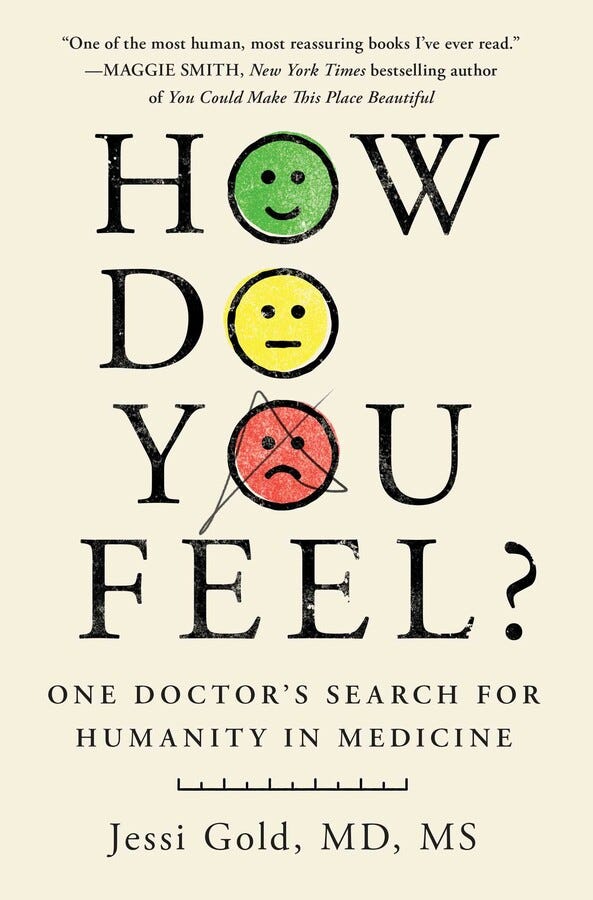

Today I’m very excited to be running a Q&A with psychiatrist Jessi Gold, whose wonderful book How Do You Feel? comes out today. Dr. Gold is the Chief Wellness Officer for the University of Tennessee System and an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. I’ve interviewed her for several stories over the years and she’s wonderful.

How Do You Feel? is a masterfully-written memoir that follows Dr. Gold and four of her patients as they navigate burnout and other mental health issues during the pandemic. I was especially drawn to Dr. Gold’s stories about growing up in a high-achieving culture and navigating perfectionism — issues many of her patients often face, too. I realized it could be extremely valuable to have a conversation for this newsletter about how perfectionism develops and what parents can do to help kids embrace balance and failure.

The book covers so much more, of course, and I encourage you to buy the book and read the whole thing. But for now, read on to learn about the subtle messages kids often get that can heighten perfectionistic tendencies, what Dr. Gold does to help her overachieving patients, and why there are so many misconceptions regarding the concept of resilience.

Jessi, in your book you talk about growing up as an overachiever. You see a lot of perfectionism, too, in the medical students and college students who are now your patients. I was definitely an overachiever, and I often try to reflect on what made me that way — because as a parent, I don’t want my kids to feel like they always have to be the best at everything. Where do you think your perfectionist tendencies came from?

I don't remember a time when my parents ever said “you have to have all A's” or “you need to do X, Y or Z,” but they did give us positive reinforcement for doing well. With allowance money based on report cards, you learn that getting an A is good. At the same time, I'm the youngest of four, and by the time I was eight, my oldest brother went to Yale and then my sister, three years later, went to Columbia — so under the age of 11 I saw that and was like, “that's what you do. You do well, and then you go to an Ivy League school.” What I learned was that that was the way of being successful. I also think my parents definitely told me I was smart — and that reinforced my caring about and valuing school.

I thought it was interesting that everyone around you had such high expectations of you — to the point that even when you truly worried about failure, nobody took you seriously. You wrote about your test-taking anxiety and poor performance on standardized tests and that people in your life didn't believe it when you said “I'm not going to pass the MCAT” — they were like, “don’t be silly, of course you are,” and that just made everything worse.

I always really struggled with standardized tests. And my parents — they were never like, “maybe we should have you talk to someone about why tests are like that for you.” They were like, “you’re really smart. Don't worry about it this much.” And I don't think they meant anything bad by it. My parents were very understanding; they weren’t judgmental. They helped where they could. But nobody really ever told me that that was something I could have talked to a therapist about. People weren't like, “the physical reactions that you're having sound a lot like pretty severe test taking anxiety.”

The expectation, especially when you get into good schools, is that you're just good at tests, and that you're going to be fine with tests. And that's a really hard expectation if you're not, right? When people think you're overreacting, and they try to tell you you're just being a perfectionist — that can be really hard. I probably would have done better having done some cognitive behavioral therapy or something around test-taking and having really thought about where that was coming from. But I found ways to adapt.

So what I’m hearing from this is that maybe it would have been helpful for your parents to have said, “what can we do to help you get through this?” And maybe also, “let's talk about what happens if you do fail. What do we do then?” It seems like it can be powerful for parents to take kids’ concerns seriously, rather than dismissing them and saying “oh, it's fine, you’ll be fine.” That said, it’s clear that your parents did sometimes take your concerns seriously — like when you asked for a tutor, they let you have one. It seems there’s a balance to be found between taking kids’ concerns seriously and communicating to them that failure is OK and sometimes to be expected.

Yeah, I felt encouraged that my parents weren't like, “you want a tutor? No, that's stupid.” I actually felt like it was helpful that they were like, “if you really want a tutor, you can have a tutor — we're not going to tell you can't have one, but also, you can get a B.” But I think that having more conversations around failure probably would have helped — or if my siblings had been more open to me about their own struggles. I was so young, and I think that they just didn't know what to talk to me about or how to connect in those ways.

Reading your book, I also I couldn't help but think about growth mindset versus fixed mindset. You wrote about being told you were smart over and over again, which is fixed mindset language — and there’s this expectation that if you're smart, you always succeed. But that kind of association is often not helpful. And I definitely had the same thing growing up. My parents didn't tell me I couldn't fail, but they definitely told me I was smart. And when I got all A's, they were so happy and praised me so much for it, so I was like, “oh, I guess this is what they want.” It was subtle — it was just seeing and hearing their very positive reactions when I did things that they liked, and thinking, “I guess I should do more of that.“ Which, I mean, of course! And why wouldn’t they be proud of me for my good grades? It's amazing how subtle parental messages can be, yet kids are sometimes interpreting them in a very prescriptive way.

I don't want parents to overthink everything they do. I don’t want them to be like, “oh no, I'm going to make my kids stress out,” or “oh no, I can't say that to them, because they're gonna take it this way.” But I think what helps is to just to be aware that you don't have to say something sometimes, and kids still interpret it. And trying to understand where kids are coming from [when they are being perfectionistic] can be helpful. Be curious. Maybe it's not anything you're doing — it's just what they're learning or thinking about themselves as a human. Think about where that's coming from, and maybe try to encourage them to value other qualities about themselves. It wasn't like I was only valued for being smart, but it felt like a primary one. I think we sometimes don't value other qualities, like by saying, “oh, that was really nice, you did a really nice thing for that friend,” or “you were a really good person today.” Pay attention to where you give positive reinforcement and maybe try to broaden that.

Right — kids learn a ton about the values we care about based on what kind of feedback we give. So let’s pivot to talking about what people can do to help overachievers. A lot of your patients have the same tendency to hold themselves to very high standards and be perfectionists. How do you help them cope with those tendencies and recognize and work through them?

A lot of it is being curious about why. Like, “oh, there might be a reason I'm doing that.” A lot of the stuff I do in therapy is prompting them to look deeper and ask questions. They might have noticed a pattern, but it might not mean anything to them. They might have zero awareness of any of the things that could have led up to it, or any of the things they're doing behaviorally to compensate for it — so the idea is to really work with them on it and say “OK, that's a behavior, or that's a thing you're struggling with — what's that about? How is that making feel, where is it coming from? Can we talk more about what it was like for you as a kid?” Really understanding how that came to be is a big part of working through this stuff.

I think understanding where you put value and what you value is important, too. Talk about the values that are central to you. Like, for me, authenticity is a huge value. Sometimes understanding how your values intersect with some of this stuff can be helpful, because it might like look like acting out, or it might look like you're really angry about something, but it could be that something is brushing up against something at your core that you really believe.

I am a psychiatrist, so I also use medication. There are people for whom it’s actually just regular anxiety, and they could use a med. And I think it's also about helping them understand what skills can be useful — like for text-taking anxiety, what can you be doing the night before? What happens if you do get anxious while you're there? I think being able to also in the moment go, “I'm feeling nervous – if I could deep breathe, or have an exhale longer than an inhale, I might feel better.”

I also loved how you talked about resilience in your book, and the misconceptions people have about the concept. There is this idea that being resilient is about ignoring or suppressing what you're feeling and just plowing through hard things — but that’s not right, is it?

I've noticed when you say the word “resilience,” people cringe. It's one of those words that is triggering — all of a sudden you're like, “oh, I just made a lot of people mad.” And a lot of that is centered on the fact that resilience has often been framed as “ignore the system problems and fix you. Here's some skills.” It comes off to people as “fix you, you're the problem,” while ignoring all of the things that are leading to it.

It’s also misunderstood as, “if you are resilient, you can handle anything we throw at you. You can come in when you're sick, you can be burnt out and work through it.” You get to these ridiculous things that don't make any sense. We're sort of in this place where we're trying to prevent ourselves from being human. But we shouldn't have to tolerate everything that comes at us. And if you can’t, that doesn't mean you're the problem. Oftentimes, it means the system is.

I used to think I could do, like, 75 jobs, and I wouldn't be tired from it or it wouldn't affect me. Now I'm very much like, “if I'm trying to do 75 jobs, I should expect that this is going to affect me.” That reframe has helped me a lot, because pretending it won't doesn’t help us, because then we think something's wrong with us if it does. School is hard. Work is hard. There's all these reasons you can have a bad day and it has nothing to do with you. I mean, sometimes it does. But inherently, it doesn't mean you're a bad person. And I think that resilience, in a lot of ways, comes off like that.

And when you're a kid, if you fall on the playground and you scrape your knee, and your parents are like, “you're okay,” what do you take from that? You’re like, “I'm not supposed to be crying about this. I'm fine.” We learn that things can happen and we should be okay. I think that that is not actually helpful, because maybe we are okay, but maybe we're not — and that's okay, too.

Excellent conversation with Dr. Gold! Perfectionism is tough, for the parent and the child. Great suggestions in here.

Thank you for this discussion. I felt like my mom perpetuated the same feeling of her own childhood which was once she did well academically, it was always expected. My twin and I were both high achieving perfectionists who got straight As until we went to college. I remember every time I ever got a bad grade on an assignment because I took criticism so personally. I can still remember papers where I got a C and getting Cs on my freshman year midterms in the spring semester. Even now 13 years later I am embarrassed to remember getting a C in Criminal Law- and my dad was a career criminal defense attorney! I figured out my study life and how to answer more bar exam style essays but failure is very difficult to deal with when being smart has been an integral part of identity.